From Auckland to Mumbai to Tehran, textile artist and aesthete Areez Katki is retracing his family’s great odyssey, for inspiration for his next collection

Instead of using a tapestry frame, textile artist Areez Katki is using pre-woven fabric and embroidering it by hand for his new exhibition. Pics/Suresh Karkera

A Parsi house is a living museum. It is a space so well-preserved in time that every household object is an objet d’art. Ceramics, wall cabinets, diwans, curios, photo frames, barnis: each item has gathered dust and been feather-dusted for decades. We’re in one such house in a baug in Tardeo, originally belonging to Minoo Lakdawala, a faded nameplate tells us. Today, his great-grandson, Auckland-based textile artist Areez Katki, is lodging here, while looking for inspiration. In a striped shirt with bell-bottom sleeves and high-waisted, tapered pants, similar to the kind his grandfather used to wear, and stitched by the same tailor, Katki, we can tell, was born in the right house and in the wrong decade.

Article by Ekta Mohta |Mid-Day

Twenty-nine-year-old Katki, and his parents (both Parsis, both accountants) abandoned Mumbai when he was 10 months old. They moved to Muscat, and then to Auckland a decade later. Katki graduated from the University of Auckland in art history, English literature and philosophy in 2012, and began knitting cardigans and scarves, and hand-embroidering shirts and silk wraps, on the side. He made only 30 pieces a year, some of which for $600 each, because he ran a workshop of one.

One of Katki’s ideas has been to depict objects found in a Parsi house on washcloths, such as ceramics and a ceiling fan

“Everything was made by me: every piece, every garment, every jumper or sweater or scarf that I embroidered or hand-knitted was made by me,” he says. “But, slowly I moved away from fashion [because] I thought about where I wanted to see my work and it wasn’t necessarily on people’s bodies. I thought that it belonged in a more permanent state on the wall, or to be looked at as a historic object. So, I’m here on an artist’s residency, to finish my first significant body of work that will go towards my debut solo exhibition.”

The exhibition will open on February 2, 2019, at Malcolm Smith Gallery, in Auckland, an ocean away. But, it will carry Mumbai in its threads, as Katki carries his heritage in his heart. “I have always attached this great romance to this house and this colony and this community,” he says. “I have more admiration and more curiosity about the Parsis of Mumbai and the Zoroastrians of Iran than I do for the very, very closely knit and introverted [Parsi] community in New Zealand.”

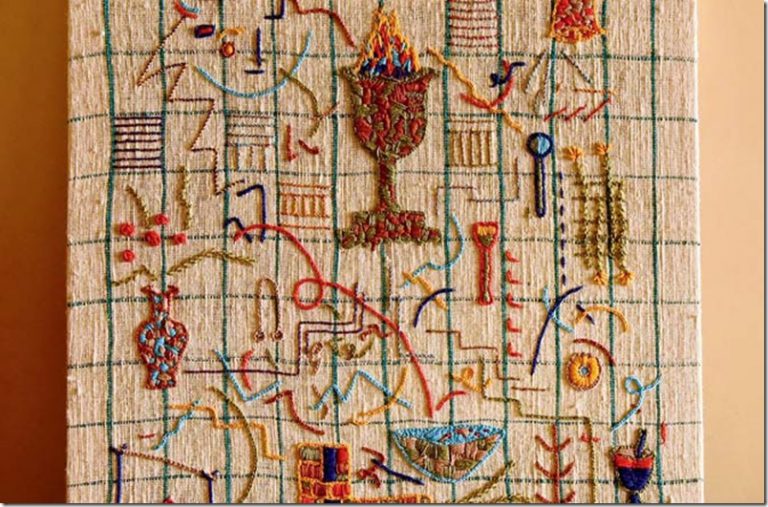

A stylistic depiction of the elements in an agiary: water, flowers (earth) and the eternal flame

His research took him to Iran recently, where he studied tapestry-making and Zoroastrian iconography. Locals would greet him with three kisses and “welcome back home.” Katki is looking at the collection from “a matriarchal perspective” because he learned how to quilt from his maternal grandmother during summer hols, and her best friend, Dolly auntie, who lives below and taught him beading and needlework. “Since I was a child, I’ve had a very close relationship with my grandmother. I am who I am because of the women in my life. They helped a lot in nurturing my love for handmade textiles.”

When he arrived in the city in March this year, he was looking at traditional Parsi embroidery such as gara and zardozi. “I did a beautiful workshop with Zenobia Davar, where I was the only guy. Everyone else was over the age of 40 and a woman. I had a wonderful time interacting with them and doing research on what is it about gara-making that was so appealing and so important to maintain as part of our heritage. But, essentially, I took the skills and used it on a different kind of cloth. Because, to me, the story is more domestic, private and intimate.

And it’s not to do with the opulence of Parsi life and society; it’s to do with the retention of memory since you’re a child and the textiles that surround you. So, I started collecting fragments of cloth from my grandmother’s wardrobe, and from this house, and from Dolly auntie’s house. And I arrived at cloths like khatkas [rags] and tea towels and doilies and tablecloths. Very humble domestic fibres, mostly cotton. I found a few rare fragments of Bombay Dyeing cloth, and some handkerchiefs that belonged to my grandfather. I was really fascinated with khatkas. I know this is something that people don’t even think about when they sweep the floors or wipe their tables, but when you look at them, there’s such an interesting texture.”

After making preliminary drawings, Katki started embroidering on these lost-and-found fabrics. He shows us a piece that features the inside of an agiary: water, flowers, a pair of tongs, a bell, the eternal flame. Another piece has embroidered ceramics and a ceiling fan. About this piece, he says, “Compositionally, I’ve picked up domestic objects from Parsi households, and implemented them on another domestic object from a Parsi household. I tried to break down the hierarchies, because this object would have wiped the subject once upon a time. And, now, I’ve put them together.” For our money, Katki is digging in the right place: within the four walls of his ancestral home. Because in a Parsi house, even the mundane is aesthetic.