![]()

‘Astad had the courage to plough a lonely furrow. He made a life of his own, on his own, and created a path-breaking dance style.’

‘Only a few in the performing arts could do what he did.’

‘A classical dancer can fall back on tradition, but Astad created something absolutely new.’

Article by Archana Masih | Rediff

![clip_image004 clip_image004]()

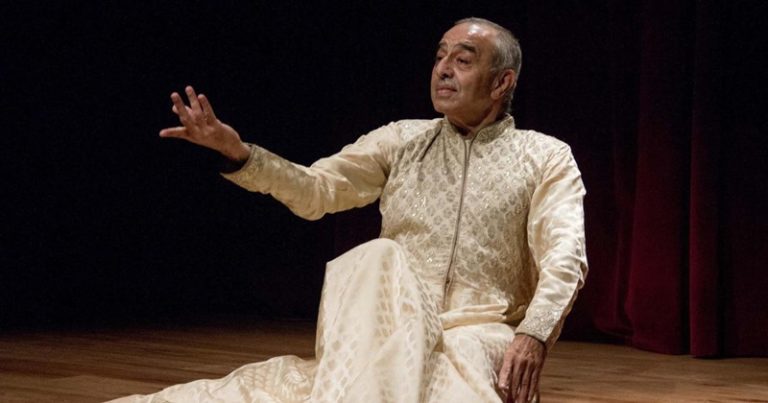

IMAGE: Astad Deboo, the legendary dancer who died after a brief illness on the morning of December 10, performs at the Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur. Photograph: Kind courtesy Ritam Banerjee

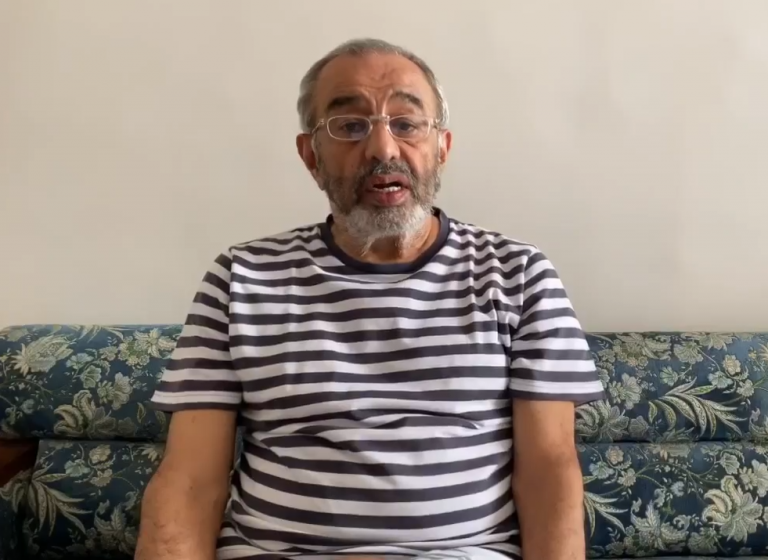

Ambassador Gautam Mukhopadhaya — who has served as India’s envoy to Afghanistan and Myanmar — shares his memories of the Incomparable Astad Deboo with Rediff.com‘s Archana Masih.

Astad is gone, but is more alive than ever. He lives on in the sunny warmth of memories.

What does one think of when one thinks of him? Three things foremost.

First, his astonishing drive, creativity and determination to carry his art forward. He believed in himself. He was ferociously committed to his art.

Second, the sheer struggle he underwent to carry his flame forward, just finding funding and organising his events. Yet, his sheer enjoyment of what he did.

Third, his extraordinary capacity to keep in touch, to talk to you every few days wherever he was. And keep in touch otherwise through photographs, images and videos.

As a friend, he was incomparable. He took the burden of friendship on himself. He didn’t leave it on you.

And he did it lightly. He would joke and tease… usually a phone from him meant that it would be a long call.

Sometimes when you were busy, you would groan. But knowing how much it meant to him, you could not decline it. He would chide you if you did not call or text back.

It was not just me. He kept in touch with all his friends. He was interested in their lives.

My world and his were far apart, but he would query in what I was working on, what I had spoken or written, and discussed issues where he felt that I could share something. Sometimes he shared gossip about my colleagues.

He would do this to all his friends. There was never a vested interest. He valued relationships.

He was very shaukeen, an aesthete, very well dressed, yet very spartan in his habits. Who can forget that incredible haircut!

He was a restless traveller. He travelled so much, to the ends of the earth, but never bored you with his exploits.

He liked good food, but would settle for anything.

![clip_image006 clip_image006]()

IMAGE: Astad during a performance. Photographs: Kind courtesy Astad Deboo/Facebook

He was very cosmopolitan. He could be anywhere. He could pick up a few words of any language and use it. He was very much a global citizen. He could be in the East, West, in high society or in a village; and he dealt with people exactly the same way, whether a domestic help or anyone else.

I got to know him when I was posted in the Indian embassy in Paris and helping with the Festival of India in France in 1985-1986.

One day Astad walked into the embassy and introduced himself. He was in Paris to choreograph the great Russian ballerina Maya Plisetskaya at the Espace Cardin, a performance space belonging to the fashion designer, Pierre Cardin. I was impressed.

I was always interested in the performing arts and had heard of him and probably seen him, but did not know him.

I have also been particularly interested in music. Our association began with sharing music.

Once, upset that I was not paying attention to her talking to him, our daughter also called Maya, marched into the living room and told him crossly, ‘He is my papa, not your papa’! He recalled this story at her wedding where he performed for her and her husband, exactly two years ago.

Our friendship built up over time. He would visit me wherever I was, Syria, Myanmar, wherever I was posted.

Sometimes I was able to help in getting local sponsorship, like when he performed with the Manipuri dancers when I was in Myanmar. I also organised a public event in Syria where he performed. I would introduce him to colleagues wherever he went.

There were a number of other colleagues in the Foreign Service who recognised his talent and drive almost from the beginning of his career and organised performances of his. Astad remembered and kept in touch with all of them.

Those who liked his dance were devoted to him.

Madhu Trehan recently wrote a piece which captured his struggles very well. I encourage everyone to read that piece simply to be kinder to artists.

It’s not that Astad didn’t get recognition. He got recognition in various circles, including the Sangeet Natak Akademi and the Padma Shri by the Government of India. But he did not get his due.

It was a challenge for him to get funding, help, from the bureaucracy, including the cultural bureaucracy and sections of the corporate world. Many saw his art as one man’s passion without much larger value. Artists need funding to keep their art alive.

When it came, it often came as charity rather than appreciation.

And yet, here was a person who came from Jamshedpur and from a minority community, who had the gumption at really a young age to take a boat to Europe and train with international masters like Pina Bausch Martha Graham, the Murray Louis Dance Company and others.

He trained in Kathak, and later Kathakali. He brought to the Indian performing arts something that did not exist before, a distillation of his explorations, and brought it national and international recognition.

![clip_image008 clip_image008]()

He suffered some rejection from the community of artistes in the early part of his career. He often spoke about the difficulty of working with classical musicians, something he liked to do. Many considered collaborating with him as compromising their own art. But later, some, like Dhrupad musicians like Bahauddin Dagar and the Gundecha brothers did.

In a way it was a blessing in disguise because it forced him to experiment in many different directions. It took him to work with the hearing impaired, the blind, street children and Manipuri drummers. He also worked with the puppeteer Dadi Pudumjee.

His art also took him to crazy locations. He would dance on monument walls and convert a table or chair into a prop for a dance. He could animate anything with his dance.

I remember him once at a home in Damascus to which we were invited. He improvised a dance with a Oud player just like that, using anything or anyone coming his way. He made it look choreographed, not ad hoc.

His mind was constantly searching for spaces, like a sensor, using body and movement in new ways.

He would walk into a room and see what he could do with it. He brought a space alive. One part of him was always searching.

Constraints in India also forced him to take his dance to audiences abroad and experiment with international groups, artists and musicians. He did some great work with Korean, Japanese and other artists and in the process expanded his art.

He found easier recognition abroad. Sometimes the environment in India was too parochial for his work. It was easier for him to be appreciated outside the country, but he never took the easy way out.

He got his due, but among a small slice of society where he was really appreciated. He was also his own publicist; his own secretary. He just lived by his dance.

Most of his performances that I saw were in later life. I would have liked to see his earlier work. I remember him doing a playful mujra like dance at one of the annual Sahmat New Year events in Delhi.

He used more props in his earlier work when he was younger and could do more acrobatic, gravity defying moves.

I have seen black and white stills of his earlier dances. He would send photos on WhatsApp. Those photos are astonishing. I feel his photographers also deserve credit for those great pictures. His costumes were spare.

I would have really liked to see some of his earlier performances when he was just coming up. Most of the later work was rooted in stillness and concentration.

One of his performances I remember well was his choreography with the hearing impaired from Chennai. He used it to highlight their different engagement with sound and the world. He worked with hearing impaired not only in India. He also had a collaboration with the Gallaudet University in Washington for the hearing impaired.

His performances with the Manipuri Thang ta artists were spectacular visual experiences. His later works were profound. He brought a Sufi quality to his dancing.

Ironically, his costumes became more flamboyant, works of art in themselves, signature angarkhas, plumes of fabric that created shapes and silhouettes of their own, living forms, like birds perched for flight.

Astad had the courage to plough a lonely furrow. He made a life of his own, on his own, and created a path-breaking dance style.

Only a few in the performing arts could do what he did. A classical dancer can fall back on tradition, but Astad created something absolutely new. It did not come from a particular style. It was entirely new.

![clip_image010 clip_image010]()

IMAGE: Astad performs at the Hotel Grand, Stockholm, June 2, 2015.

In attendance were then President Pranab Mukherjee, the Swedish king and queen, the crown princess, Indian MPs and business delegations.

My last conversation with him was on December 2. There was WhatsApp group of his close friends where his sister sent out health updates. The initial updates were encouraging and then it started getting darker.

He worried for his medical insurance cover, whether it would be large enough for his treatment. The whole period between the detection of illness and passing was barely over two weeks.

On the morning of December 2, concerned about a thread of messages on him on sleeping badly, I texted him asking if he was well for his next chemo.

He called back immediately to say that he was feeling better, but was simply unable to sleep.

What struck me was that his voice was not sounding good, but he did not know or realise.

I didn’t want to make him talk too much because I wanted him to conserve every bit of his energy.

He called back after a few minutes to say that the doctors had told him that it was too far gone for chemo. One suggested Ayurveda. It had been known to work miracles in some cases.

It was sad that it happened over COVID. I asked him if I could visit him in Mumbai. His answer was the trademark ‘No darling’.

That was our last conversation. He sounded resigned. He fought hard, but he lost. He did not rage or rant.

The messages became less and less. No news meant bad news.

![clip_image012 clip_image012]()

IMAGE: A tribute at the Ojas Art Gallery.

I’m sure there are people working on documenting and archiving his work. This was his one big dread and lament. He was too busy with dance to bother about his legacy. Now, it mocked him.

He had a foundation that was mostly to help his dancers, but he did not to get down to putting together a tangible legacy.

He talked to me about the fear of not leaving behind anything once he exits stage. To do this he needed funds.

I was sincerely hoping that he would recover and realise that he has to retire and focus on archiving his work for posterity, perhaps a museum.

I never thought that he would go. I realise that I will never get that telephone call from him again.

Gautam Mukhopadhaya served as India’s ambassador to Afghanistan, Syria and Myanmar.

Pestonjee Bomanjee’s connection to Rudyard Kipling is quite fascinating. Bomanjee was the first Indian student to study art under Kipling’s father, John Lockwood Kipling, who was appointed as head of the department of artist-craftsmen at the ‘Sir JJ School of Art and Industry’ in 1865. The school was established in Bombay in 1853, by another Parsi Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, a wealthy China Merchant. Rudyard Kipling was born in the principal’s bungalow on the grounds of the Sir JJ School of Art and a bronze plaque commemorates this event.

Pestonjee Bomanjee’s connection to Rudyard Kipling is quite fascinating. Bomanjee was the first Indian student to study art under Kipling’s father, John Lockwood Kipling, who was appointed as head of the department of artist-craftsmen at the ‘Sir JJ School of Art and Industry’ in 1865. The school was established in Bombay in 1853, by another Parsi Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, a wealthy China Merchant. Rudyard Kipling was born in the principal’s bungalow on the grounds of the Sir JJ School of Art and a bronze plaque commemorates this event.