Shirin Vajifdar, who died on September 29, 2017, exhibited an unusual love for classical dancing from childhood and defied taboos to train in multiple classical dance forms.

Article by Sunil Kothari | The Wire

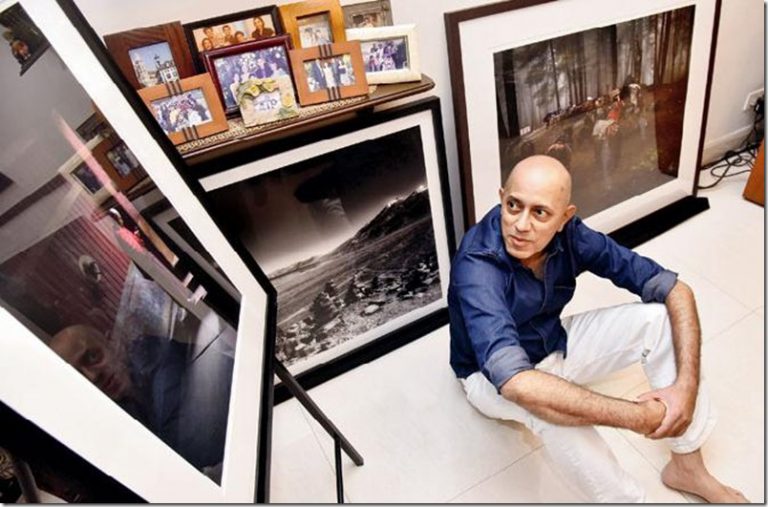

Shirin Vajifdar. Credit: Mulk Raj Anand: Shaping the Indian Modern (MARG)

In the early 1930s, it was inconceivable that a young girl from the Parsi community would take up classical dancing. But that is what exactly Shirin Vajifdar did. The doyen of Jaipur Gharana Sunderprasadji had moved to Mumbai (then Bombay) and started teaching Kathak to the Poovaiah sisters from Coorg. Shirin studied under the great maestro and went for further dance training to Madame Menaka’s Nrityalayam dance institution in Khandala, near Bombay.

Her contemporaries at Nrityalayam were Damayanti Joshi, Shevanti Bhonsale and Vimla. Shevanti later joined Ram Gopal’s troupe. During those years, a young guru of Manipuri from Calcutta, Bipinsingh had joined Nrityalayam to teach Manipuri. There was another Kathakali teacher and dancer, Krishnan Kutty, who taught Kathakali. Shirin studied all the three forms and with excellent memory, mastered the complicated bols and mnemonics of Manipuri.

Madame Menaka had started choreographing dance-dramas with the help of Kathak gurus Gauri Shankar, Ramnarayan and Pandit Ramdutta Mishra. She included young dancers in those dance-dramas such as Menaka Lasyam and Kalidasa’s Malavikagnimitram. Madame Menaka used Manipuri and Kathakali dance forms for a court dance sequence in celebration of King Agnimitra ‘s victory over enemies. Shirin was thus exposed to early attempts of creating group works.

Shirin then taught dance to her two sisters Khurshid and Roshan and they started performing together as the Vajifdar sisters. They were often threatened by conservative Parsis who would disrupt their shows by throwing eggs and stones, but Shirin was not afraid and carried on receiving support from elite sections of the Parsi community.

Shirin and her sisters were contemporaries of Poovaiah sisters, Sitara Devi, Tara Choudhary, Mrinalini Sarabhai, Shanta Rao, Vyjayntimala, Ritha Devi and became quite well known. They were often invited to give performances for charitable causes. They gave private tuitions to young girls from their community when dance became acceptable as an art form. As a teacher, Shirin was a strict disciplinarian, recall her students. One of her students was a bright dancer, Sunita Golwala, who later moved to London. Another student was Jeroo Mulla.

Shirin was married to Mulk Raj Anand, the celebrated author, founder and editor of the quarterly magazine Marg. Khurshid married the renowned painter Shiavax Chavda and Roshan married Hiranmay Ghosh, a chiropractor, and later settled in Kodaikanal. She won a government of India scholarship and went on to study Bharatnatyam under Chokkalingam Pillai in Chennai. She won fame as a briliant Bharatnatyam dancer.

In 1954, Shirin was invited by the film director Kishore Sahu to choreograph a dance sequence for his film Mayurpankha, for which Khurshid and Roshan danced for a duet sung by Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhonsle. The music was composed by Shankar Jaikishan. The film won a Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

The three Vajifdar sisters – Khurshid (left), Shirin (middle) and Roshan (right) in a Marwadi Rajasthani folk dance. Courtesy: Jyoti Chavda

In 1955, a big delegation of dancers and musicians was sent to China, which included Shirin and Guru Krishnan Kutty, along with Indrani Rahman. Shirin performed the mythological story of Mohini and Bhasmasura with Kutty.

In those years, there was no video shooting of performances. Therefore, there are no recordings of Shirin and her sisters dancing. Films Division had made one small documentary of her performing a Bharatnatyam dance, which is now lost.

I came to know Shirin around the year 1957. By that time, she had retired from performing. I had met Mulk Raj Anand the same year. Mulk often invited artists and writers at his 25, Cuffe Parade residence. I used to attend the soirees – meeting painters and writers. Mulk encouraged me to write on dance and suggested that I should attend the All India Dance Seminar at Vigyan Bhavan in New Delhi in April 1958. There, he introduced me to Roshan Vaijfdar, who was to present a paper on Nayikas and Gita Govinda. Shirin had joined us and we met Devika Rani and the Russian painter Nicholas Roerich, whose muse was Roshan. He had done a few portraits of Roshan. Shirin and Mulk were very close to Devika Rani and Roerich.

I often visited Mulk’s residence in Mumbai when I was assigned to write the book on Bharatnatyam for Marg. Shirin was a gentle person and always kept a low profile. She was writing her autobiography and would sometimes read out few paragraphs which were quite moving in terms of how the sisters suffered humiliation when they took to dancing. She would sometimes tell interesting stories about Ram Gopal who used to stay at Oceana building on Marine Drive. She recalled that he was a charismatic and handsome dancer with a gift of the gab. He would invite the sisters to learn Bharatnatyam from him.

Shirin was invited by Shamlal to write reviews of dance for the Times of India. By then, I was writing reviews for the Evening News of India. Shirin and I used to attend many dance performances together. She had a vast range of references, having seen many dancers and dance forms. She kept all her reviews carefully in a scrap book and advised me to keep a copy of my reviews. She was very meticulous. Her approach was to encourage young dancers and she wrote encouragingly about Yamini Krishnamurty, Sonal Mansingh (nee Pakvasa), Kanak Rele, (nee Divecha), Protima Bedi, Sanjukta Panigrahi, Kum Kum Mohanty, Shobha Naidu and other dancers from the south. Her approach was one of constructive criticism. Dancers still remember her kindness and have collected reviews written by her.

We used to visit Lonavala on weekends, where Mulk had a bungalow. I spent many weekends with them. Shirin would often speak of dancers like Indrani Rahman, who was her favourite and a close friend. She was fond of the Jhaveri sisters and traditional gurus Mahalimgam Pillai, Govind Raj Pillai and Kalyasndaram Pillai. By temperament, she was a happy dancer having performed and seen best of the times. As a partner of Mulk, she was a gracious hostess and never asserted her status as his wife or as a dancer.

After I left Mumbai for Kolkata to teach dance at Rabindra Bharati University and later at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, I used to call upon her. After Mulk’s passing away, she had moved to a small apartment where her niece Jyoti looked after her. She had been keeping well. I used to prod her to complete her autobiography as I knew it would be a valuable document of dance history and of her pioneering work. Shirin will be missed by her large group of admirers and dancers.

Sunil Kothari is a dance historian, author and critic, and fellow, Sangeet Natak Akademi.